An integrated nebula catalog

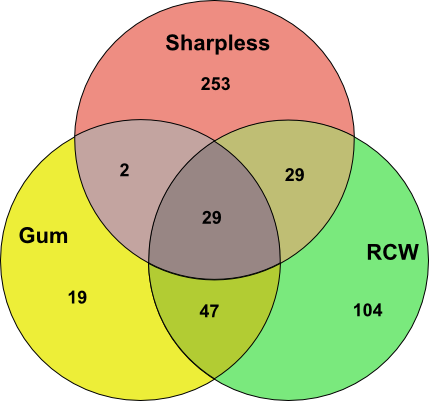

In my last blog post, I announced that I had completed my commentaries on the Sharpless, RCW and Gum nebulae and pointed out that there is considerable overlap between the three catalogs.

It was a logical next step to create an integrated catalog combining all three catalogs, removing duplicates and adding cross references.

I've gone further than that, however. The new integrated catalog attempts to identify all the extended areas of nebulosity visible in Douglas Finkbeiner's full sky hydrogen-alpha map. This is not a complete hydrogen-alpha nebula catalog, however, for three main reasons:

- the Finkbeiner map combines three very sensitive but low resolution hydrogen-alpha surveys and so smaller nebulae are often not visible unless they are very bright,

- there is at least some hydrogen-alpha emission visible in every region of the sky and the cut-off point for inclusion in a catalog is arbitrary, and

- these are clouds, after all, with indistinct boundaries and complex internal structures - where one nebula stops and another begins is unclear, especially in the absence of detailed distance data.

Neverthless, I was able to expand considerably beyond the 483 distinct objects listed in the Sharpless, Gum and RCW catalogs. There are 733 nebulae listed in the full integrated catalog.

The catalog includes the object name, catalog name and galactic coordinates (l and b) for a central point for each object. Tn order to make the catalog more useful for astrophotographers, it also gives the central point in equatorial coordinates (right ascension and declination) as well as a radius in arcminutes and the constellation within which it is located.

I have provided cross reference numbers for the nebulae in the Sharpless, Gum and RCW catalogs. For the primary name I have preferred the Sharpless designation followed by the Gum designation and then finally RCW.

In addition to the Sharpless, Gum and RCW catalogs, the integrated catalog also includes the BFS nebulae and a large number of the nebulae listed in the 1976 paper by Dubout-Crillon as well as a small number of other sources.

There are 78 nebulae that I could not find in any catalog in SIMBAD and for convenience I have designated these GMN 1 to GMN 78 (Galaxy Map Nebula catalog). In some cases these are faint nebulae and in others, nebular regions that encompass a number of the nebulae in the other catalogs. Inclusion in the GMN catalog does not mean that the object is a new discovery as many catalogs still are not available from SIMBAD and many individual studied nebulae have not been gathered into a catalog. At some point I'll write a commentary on the GMN objects and describe what information is available on them.

You can download the integrated catalog in Excel format here.

You can also view the integrated catalog data overlaid on a false colour version of the Finkbeiner map in the Milky Way Explorer. The circles surrounding the nebulae are colour coded:

- yellow marks a nebula in the Sharpless, Gum, RCW and BFS catalogs,

- orange marks an HII region in another published catalog,

- green marks an unknown nebula listed in the Galaxy Map Nebula (GMN) catalog, and

- cyan (blue-green) marks other prominent objects not in the integrated catalog but visible in the Finkbeiner map: stars, planetary nebulae or galaxies.