As I write this, the scientific equivalent of a sold-out U2 rock concert is taking place at the ESTEC complex in Noordwijk, Netherlands. Some 400 scientists are gathered to hear the results of the first year of operation of the Herschel infrared space telescope. I blogged about Herschel and Planck after the two space telescopes were successfully launched last year (The king is dead - long live the king).

Because of the huge scientific interest in the conference (which is discussing results under strict media embargo), attendance had to be limited. I've been following Twitter updates from two scientists attending the meeting (Dave Clements and Brian O'Halloran) to get at least a glimmer of what is going on.

Unfortunately both scientists are attending the extragalactic sessions, so information about the Milky Way results is limited. A news conference is scheduled for later today and I hope more information will be available afterwards.

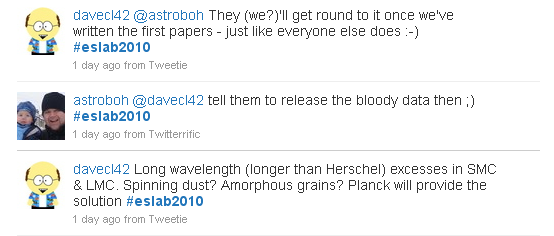

Yesterday there was a revealing Twitter exchange between the two scientists (as it happens Clements was sitting immediately in front of O'Halloran in the meeting room, but hey this is Twitter and the exchange was as much for their "followers" as themselves).

(Read the exchange from the bottom up.)

The exchange was specifically about the plan for a long delay in the public release of the Planck microwave data, but it might equally apply to the Herschel results. For example, the images collected in the Hi-GAL survey of the inner galactic plane are not scheduled for release until two years after the telescope was launched.

Clements suggests a reason for the delay, which is that the scientists immediately involved in the telescope projects are hoarding the data until they have written their papers.

Given the intense competition between astronomers, data hoarding is perhaps not surprising, but is it true that "everyone" does this as Clements states in his tweet? I'm not a professional astronomer, but it appears to me that NASA has a different policy for some of its space telescopes. In particular, Spitzer infrared data appears to be available as soon as it is acquired and archived. (Correction: Sarah Kendrew informs me that this depends upon the project and at least some of the Spitzer projects have a 12 month proprietary period.)

The fact that scientists involved with major telescope projects have a competitive advantage is not new. US scientists dominated astronomy for much of the twentieth century in part because the best telescopes in the world were located in California for most of the century. Even Jan Oort's famous paper on the rotation of the Milky Way was based largely on data begged or borrowed from US scientists.

The Internet has changed the dynamic, however, because now scientific data is routinely archived online. It is easier to share the data than not. Scientists involved with major projects need to go out of their way to password protect their data if they want it to remain private.

As the infrared astronomer Sarah Kendrew pointed out in a recent blog post (Setting free the Data), a huge number of scientific papers are now published by scientists using public data archives. In my view, this trend is a good thing and scientific data should be made available as soon as possible so that scientists without immediate access to the instruments (like Jan Oort) have the opportunity to make major discoveries.